PRE-VEDIC

Most studies point out that modern Homo Sapiens developed in Africa some 200,000 years ago. Dating the earliest human migration to Indian mainland remains a matter of dispute but the most significant Indo-African resettlements took place around 70,000 years ago.

While archaeological evidence indicates inhabitation in Andaman Islands for more than 2200 years, genetic and cultural studies suggest the Andaman natives – Australoid-Malanesian settlers may have been isolated from other populations during the Middle Paleolithic era up to even 26,000 years ago!

Photo: Maurice Vidal Portman (1861-1935) – Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

“An early (staged) photograph to show Great Andamanese women (and the odd male) with a wide variety of hairstyles and body painting patterns. Clearly visible are only the wide variety of hair cuts. Notable also on the extreme left and right two women with bands for carrying infants. The people to the left of the centre pole are said to be showing body paint signifying mourning, those on the right celebratory paint. The girl, second from the right, in the middle row is said to be painted in red ochre as a sign for rejoicing.” – Citation from Clothes, Clay and Beautycare (of Great Andamanese people), by George Weber

Palaeolithic Indian inhabitants worshipped idols and deities, sacred status of animals including cows, peacocks, cobras, elephants, and plants like pipal, thulasi, and neem. The aboriginal people of India traditionally lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and mostly wore little (or no) clothing, made of animal skin and vegetation. Ancient Indian Adivasis much like other Negrito, Australoid & Mongoloid natives wore elaborate jewellery in form of stones, animal claws, feathers etc.

INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION (3300–1500 BCE)

The Neolithic age marks the onset of urban Indus Valley Civilisation – one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia, which also meant access to fibres like cotton, flax, and linen. Archaeological remains of silk firers from Harappan sites suggest people also wore silks textiles and knew silk farming techniques. Indus valley figurines wear elaborate jewellery including necklaces, anklets, earrings, and bangles in stone, terracotta, gold, copper/bronze. Bead jewellery was popularly traded in this era. An Indus Valley female skeleton on display at the National Museum, New Delhi, wears a bangle on left hand. People covered their lower body with a short rectangular wrap tied with waist bands/belts. Figurines of this era also feature intricately detailed hairstyles and headgear, including flower decorations and a female in a turban. Men left their hair long, at times tied into buns. Nudity was a natural and acceptable notion in Indus Valley. While Varna system itself didn’t exist in Harappa-Mohenjo Daro cultures, it’s noteworthy that the priest-king figurine is more decorative than other figurines which are chiefly unclothed. Clothing was clearly established as a medium to express social status.

Indus people worshipped idols including Shiva lingam and select animals and plants. The Pashupati seal from this era is viewed as a possible representation of a “proto-Sivan” figure. Inhabitants of Indus Valley Civilisation are widely regarded as proto-Dravidian due to cultural similarities and indications of genetic studies. Many linguists in particular propose that Adi Dravida or Ancient Dravidians were spread throughout the Indian subcontinent before the influx of Indo-Aryan languages. Some historians alternatively hypothesise that Indus people along with migrants from Steppe grasslands form ANI (Ancestral North Indians) whereas Indus Valley people who moved South and mixed with hunter-gatherers make up ASI (Ancestral South Indians). The recent Keezhadi excavations in Thamizh Nadu has unearthed Harappa like urban sites dating to Sangam era, strengthening the Indus-Dravidian ties.

AUSTRO-ASIATIC & SINO-TIBETIAN

Late Neolithic period sees the fall of Indus Valley Civilisation and migrations of Austro-Asiatic populations in North Eastern India till around first millennium BCE. Crossovers in ethnicity and language are observed by studying ethnic origins and linguistic affiliations, for example, Nicobarese considered to be Mongoloid speak Austro-Asiatic language, and among Bhils, Gonds and Oraon Adivasis are classified as Australoid groups, Bhil tribe speak Indo-European languages whereas Gondi and Oraon speak Dravidian languages.

The decline of Indus Valley Civilisation is followed with agrarian Indo-Aryan nomadic settlements in North-Western India referred as Arya Vrata in Vedas. The religion & language of Vedic people had strong traces of Indo-Iranian cultures, especially in cases of Vedic Sanskrit’s relations with Avesta, and Soma cult and the fire worship, both of which are preserved in Zoroastrianism. The Vedic religion comprises of Vedic Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas and early Upanishads.

VEDIC PERIOD (1500-600 BCE)

The first literary trace of the word “Shudra” is found in Rig Veda.

11. When they divided Purusa how many portions did they make?

What do they call his mouth, his arms? What do they call his thighs and feet?

12. The Brahman was his mouth, of both his arms was the Rajanya made.

His thighs became the Vaishya, from his feet the Shudra was produced.– Rig Veda 10.90.11–12

Note: The term Varna in Vedas may refer to any of colour, outward appearance, tribe, race, or classification, whereas it strictly refers to social hierarchy (based on labour) in Dharmashastras like Manusmriti which were written later.

Rig Veda structures a two-fold Varna system on basis of tribe and lineage – Arya Varna and Dasa Varna. Vedic nomads, culturally and genetically different from Indus valley people regarded themselves as Arya and the non-Vedic indigenous people of India were labelled Dasa or Dasyu – translates to barbarians, demons or slave in Vedic hymns depending on contexts of usage.

Several Rigveda hymns glorify white skinned Aryans defeating dark skinned Dasyus. Krishnam Vacham [Black skin: Vedic Sanskrit] was written off as impious.

“The mighty Thunderer with his fair-complexioned friends won the land, the sunlight, and the waters.”

– Rigveda, Book 1, Indra 100.18“Indra in battles help his Āryan worshipper, he who hath hundred helps at hand in every fray, in frays that win the light of heaven.

Plaguing the lawless he gave up to Manu’s seed the black skin;”

-Rigveda, Book 1, Indra 130.8

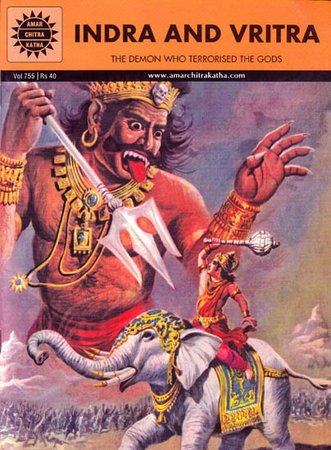

Amar Chitra Katha depicting Aryan Indra fighting a dark-skinned mustached Dasyu – on back of a fair skinned elephant. Note: This image is a contemporary portrayal and Vedic people didn’t wear silk brocades. Silks gain prominence only after 1st century BCE.

While Rig Veda sanctions purity of fair-skinned lineage, later Vedic texts relate the notion of purity through hierarchy decided by profession. Evidence of clothing in this era comes only in form of Vedic knowledge which was verbally transferred to pupils by Brahmin teacher. Vedic people did not sew their clothes. Clothing was chiefly minimal and draped, however description of rich ornaments and jewellery are mentioned.

Some translations of references of clothing items in Rig Veda include:

- Adhivastra – Veil

- Kurlra – head-dress or head-ornaments

- Andpratidhi – (any) covering of body

Atarva Veda also mentions:

- Nivi – Innerwear

- Vavri – covering of body

- Upavasana – Veil

- Kumba, Usnlsa, Trilta – Head-dress

- Updnaha – Footwear

- Kambla – Blanket

BRAHMINISM (c. 600–200 BCE)

The Vedic religion flourished under the Kurus of Kurukshetra as acknowledged by Atarva Veda. Rig Vedic Varna system of Arya and Dasa is replaced with four-fold Verna system on basis of labour in this period. The Brahmin priesthood and Kshatriya aristocracy dominated the Arya commoners (now called Vaishyas) and the Dasa labourers (now called Shudras). By late Vedic period, the Brahmin literature subjected Shudras to social ostracism for being guilty of sins committed in a previous life and they could expect rebirth into one of the “pure” upper-caste by submitting themselves as the slaves of top three Verna hierarchies, thereby marking the onset of the longest surviving apartheid in world history – the Brahminical caste system comprising of Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaisya, Shudra and Avarna/Outcaste (in order of hierarchy.)

Since Vedic times, people from many strata of society throughout the subcontinent adapted to established Brahmanic social codes – leading to Sanskritisation of India. By late Vedic period, Brahminical kingdoms control a significant portion of Northern India. Mahajanapadas arise from late Rigvedic kingdoms by 600-500 BCE. Some renowned Brahmin kingdoms of Iron Age era included Nanda Empire, Magadha, Pauravas, and Taxila.

BUDDHISM & JAINISM

Mahavira (c. 549–477 BCE) and Buddha (c. 563-483 BCE), challenge the orthodoxy of the established Brahminical rituals, repudiated the authority of the Vedas, and rejected the Brahminical Varna system as well as Vedic rituals of animal sacrifice, thereby leading to the rise of two new religions Jainism and Buddhism.

MAURYAN EMPIRE – (300 BCE – 187 BCE)

Chandragupta Maurya establishes Mauryan Empire by overthrowing Nanda Empire with assistance of Chanakya. Megasthenes, the Greek historian upon his visit to India writes that there are no slaves in Mauryan empire. This could be a possible reference to ancient European style commercial slaves, since Arthashastra of this era otherwise mention slaves. Chanakya’s Arthashastra is probably among the first of shastras to provide some kind of rights to Dasas, the antithesis of Aryas. Verses of Arthashastra punishes prejudice towards Dasa including sexual exploitation, thereby adding light to the status of Shudras in preceding Brahminical socities of Mahajanapadas.

Employing a slave (dasa) to carry the dead or to sweep ordure, urine or the leavings of food; keeping a slave naked; hurting or abusing him; or violating the chastity of a female slave shall cause the forfeiture of the value paid for him or her. Violation of the chastity shall at once earn their liberty for them.

— Arthashastra, Translated by ShamasastryA slave (dasa) shall be entitled to enjoy not only whatever he has earned without prejudice to his master’s work, but also the inheritance he has received from his father.

— Arthashastra, Translated by Shamasastry

A Mauryan statue depicting mauli (turban), kayabandh and loin cloth worn with coiled earrings.

Clothing in Mauryan era was primarily unstitched and comprised of two pieces. There’s no evidence of single long garment draped on both upper and lower body like the modern sari. The loin cloth worn in Vedic period was continued to be worn in this period. The Greek influence during the Mauryan era also contributes to the earliest Indian breast-covering garment – Pratidhi.

Mauryan Womens Costumes:

Uttariya: Upper cloth of printed cotton worn crosswise on the head.

Kayabandh: Embroidered flat cloth band, pattika style, worn in a looped knot with fringed ends.

Mekhala: Six-stringed hip belt of gold or silver beads.

Lambanam: long necklace made of chains held at intervals by flat bands, phalakahara style.

Kantha: Short necklace of five strings of beads in gold or silver.

Karnika: Trumpet-shaped earrings.

Kangan: Ten bracelets adorning each hand.

Baju Band: Decorative armlets worn on upper arms.

Kara: Anklets of twisted wire worn on both ankles.

Sitara: Star shaped forehead ornament of gold or silver with a stamped pattern.

Mauryan Mens Costumes:

Antariya: Kachcha style, both equal ends being taken between the legs after knotting the front; these ends are then held diagonally, fluted and tucked into the waist at the back to hang between the legs up to the ground

Uttariya: upavita fashion, worn across the chest and over the left shoulder

Kayalbandh: muraja style, drum-headed knobs at the ends, tied in a looped knot

Baju Band: armlets with elaborate incised pattern

Kangan: several bracelets on each wrist

Karnika: trumpet-shaped earring or karnaphul

Mauli: turban of printed cloth held by decorative bands wound over the top knot of hair and at the side of the head

Mauryan Warrior Costume:

Antariya: knee-length, worn in kachcha style with fluted end tucked in at centre front

Tunic : one of the earliest depictions of the cut and sewn garment; it has short sleeves and a round neck, full front opening with ties at the neck and waist, and is hip length

Boots : fitting to the knees Head band: tied at the back over short hair

A broad flat sword with cross straps on the sheath is suspended from the left shoulder.

Mauryan empire reached its prime at a time when Ashoka conquered (almost) entire India and converted to Buddhism after the Kalinga war in 236 CE. Chandragupta Maurya embraced Jainism after retiring. Buddhism becomes the Ashokan state religion. Vedic gods steadily lose relevance without patronage of the state in this period whereas the message of Buddha reaches off shores. Ashoka bans animal sacrifice rituals, which affected the influx of wealth and gifts for Brahmins in a new egalitarian social order in which they weren’t at top of hierarchy any more.

BRAHMIN COUNTER REVOLUTION – 187 BCE

Pushyamitra, a Brahmin Mauryan general assassinates the last Mauryan Emperor Brihadratha Maurya to establish Shunga empire whose inscriptions reach as far as Ayodhya. Pushyamitra not only revived Brahminical supremacy by reestablishing four-fold Varna system and animal sacrifices Yajas prohibited by Ashoka, but he also cruelly persecuted Buddhists. Vibhasa, a 2nd century Buddhist text, states that Pushyamitra burned Buddhist scriptures, killed Buddhist monks, and destroyed 500 monasteries in and around Kashmir.

Compilation of Ramayana and Mahabharata begins in this period with patronage of Brahmin kings and will be completed over approx. 600 years in Gupta period. Brahmins also responded with Dharmashastra (including Manusmriti) in this period to reclaim the authority of Vedas. Most of the basic ideas and practices of arising classical Hinduism will derive from the new Smriti literature.

SHUDRAS IN MANUSMRITI

“A Brahmana may confidently seize the goods of (his) Sudra (slave); for, as that (slave) can have no property, his master may take his possessions.” – Manusmriti 8.417

“Brahman men can marry Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaish and even Shudra women but Shudra men can marry only Shudra women.” – Manusmriti 3.12

“In case a Brahman man marries Shudra woman, their son will be called ‘Parshav’ or ‘Shudra’ because his social existence is like a dead body.” – Manusmriti 9.178

“Sudras who live according to the law, shall each month shave (their heads).” (Manusmriti 5.140)

Royal couple in Shunga period 100 BCE – The clothing of this period (along with Gupta costumes) is somewhat standardised in large-scale in depiction of Puranic Hindu gods.

EARLY PURANIC HINDUISM – (250 CE – 500 CE)

Ramayana and Mahabharata are compiled over a period of six hundred years and the writing was completed by 300 CE – 400 CE. Ramayana and Mahabharata are compiled as Itihasa (Sanskrit: History) whereas Purnas narrate the interactions of Vedic gods with people and demons. The early Puranas like Markandeya Purana, Matsya Purana, Vayu Purana and Vishnu Purana are roughly compiled from 250 CE to 500 CE. Few other Puranas written in this era like Brahmanda Purana, Vamana Purana and Kurma Purana and Linga Purana are completed till around 850 CE – 1200 CE. Early Puranas were written in retaliation to popularity of Buddhism, with intent to reach out to the masses including tribals through simple story telling. However the Dharmashastra (treaties of Dharma) compiled in this period ordered the Vedic knowledge was exclusively retained only within upper-caste community member, who will be allowed to marry only within upper-caste community.

The epics and Purnas weren’t written by a single author but many, and further edited and reedited by several other authors – however the authors were all Brahmins. While the non-Brahmins worshipped even Yakshas by late Vedic period (which made no intellectual sense to Indra-centric Vedic knowledge), Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva emerge as the new popular gods under the new Puranic reiligion.

KUSHANA EMPIRE (30 CE – 375CE)

The Kushanas bring in multicultural influences of Scythian, Hellenistic and Greek to Indian subcontinent. A headless statue of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka found in Bactria near Afghanistan shows him dressed in trousers, boots, tunics and overcoat. One of the most important costume development in this period was a rectangular cloth garment draped over both lower body and upper body – the sari drape, Roman influenced. Trade with China was directly established through silk route, providing access to exotic silks in colours of blues, gold, bronze, green, crimson, pink, red, yellow, yellow-green, and browns.

Kushan Royal Costume:

Chugha : calf-length overcoat with a wide richly embroidered border down the centre-front opening, hem and edge of long sleeves (probably ruched)

Tunic : Kurta-like long garment

Chalana : baggy trousers tucked into calf-length padded boots

Prince Siddhartha, Gandhara School of Art depicting the costumes of Brahmin priests and royal/court men.

Kushan men wore stitched calf length tunic. Owing to the Roman influence of Kushans Antariya in the era is worn sari-like, tied in front, while one end is passed between the legs, pleated and tucked in at the back, the other end is partly pleated and tucked in at the front, then wound around and worn over the left shoulder.

Mathura School of Art. Costumes of Kushan women include: Antariya (lehenga style) : simply wrapped around and tucked in at the left

Anatriya (sari style) : worn in the kachcha style, the other end being taken across the body and over the left shoulder

Uttariya : thrown casually over the shoulders

Tunic : with front opening, held at the neck by button; long ruched sleeves have ruching held by jewelled bands or buttons; tunic is form-fitting

Mekhala : four-stringed girdle with clasp and decorative leaf at the centre

Hara : one long pearl necklace worn between the breasts and one short one with a pendant

Kundala : large ring-type earrings

Head-dress : chaplet of leaves or turban with a central flower worn around the top knot of hair

SATVAHANA DYNASTY (221BC-218AD)

The Budhism and Jainism continued to decline under Satvahana rulers. Jain Satvahana king Simukha adopted Brahmin orthodoxy and performed Rajasuya and Ashwamedha sacrifices. Post Satavahana dynasty, Andhra Pradesh was divided into several kingdoms, such as Ikshvakus, Brihatpalayanas, Anandas, Salankayanas, Pitrubhaktas, Matharas, Vasishtas etc, who were all Orthodox Brahminism, Vaishnavite or Shivite rulers.

Woman wearing Pratidhi (breastband) Ajanta Caves, Maharashtra. By this period, there was considerable influences from the West, the Greco-Roman notion of covering breasts finds popularity in Indian subcontinent.

Costume of Dancing Girl (Ajanta Caves, Maharashtra):

Cholaka: fitted choli-type blouse with an apron front; the long sleeves are of dark red brocade, while the middle is of white silk probably tied at the back with ribbons that are visible

Antariya: worn in Lehenga style, is of silk with purple, green and yellow stripes with lozenge patterns in white

Muktavali: three stringed pearl necklace

Hara: necklace of large beads

Valaya: two simple and one ornamental bangle on each wrist

Kancala Kundala: elaborate earrings with pendants

Mukuta: tiara of gold

Hairstyle: large bun at the nape with flowers and several strings of pearls or gold chain wound around and held by brooches

ARYA-DRAVIDA CULTURAL FUSION

Ancient Thamizh classical work Sangam literature (which also included several women poets like Avvaiyar, Mudatamakkanniar, Kaakkaippaadiniyaar, Naachchellayaar, Naagaiyaar, Nanmullaiyaar, Ponmudiyaar, Ilaveyiniyaar and Nappasaliyaar,) was compiled between 400 BCE until 300 CE under the patronage of early Pandya, Chola and Chera kingdoms. Sangam texts, primarily secular in nature account details of early Dravidian religion which is non-Vedic in origin. The Brahminical four-fold caste system wasn’t practised socially in this era. The earliest reference of Paraiyar, drummers classified as Adi Dravida (Dalits) in modern India, occurs in a poem by the Sangam poet Mangudi Kilar in 2nd century CE, however any labelling of caste identity (social hierarchy) to the profession itself does not occur until the reign of Rajaraja Chola in 1100 CE.

In ancient Thamizh grammatical works Tholkappiyam, Murugun was described as the favoured god of Thamizh people and Shiva had the status of supreme god. Early iconography of Dravidian gods Murugan and Shiva and their association with native flora and fauna goes back to Indus Valley Civilization. It’s remarkable to note that Vedas find no reference of Shiva but Vedic deity Rudra is mentioned as Shiva in later post-Brahminism texts. Thirumal, Amman/Mariamman, Valli, Wanji-Ko & Kotravi were other popular ancient Dravidian gods. The architecture and style of Sangam period brick temple excavated at Salavanakuppam near Mahabalipuram, is different from the norms of Bhramnical Shilpa Shastra.

DARK AGES OF DRAVIDAN HISTORY (300 CE – 700 CE)

The Kalabharas invade and displace the three Tamil kingdoms by 300 CE – described as Dark Age in Thamizh literature. Though Kalabharas conquer South India as Jains, they later preach Shaivism and Vaishnavism, possibly influenced by Puranic religion of late Gupta period. Kalabhara kings patronage Murugan who is now referred as Skandha and King Achyutavikranta, a Vaishnava becomes Tirumal devotee and Tirumal is merged with Vishnu, Amman with Parvati and Wanji-Ko with Indra in this period. Kalabhra coins dating towards the 600 CE employ both Prakrit and Thamizh in their inscriptions. This period represents the most significant religious fusion between ancient Dravidians and Indo-Aryans. However, this synthesis of religion is also widely criticised on grounds of Dravidian gods being hijacked or appropriated into Puranic and Vedic gods, and modification of Dravidian cultural history and knowledge. The rule of Kalabharas is ended by counter-invasions by Pallava, Pandya and Chola kings. Pallava king Mahendra Varman, a Buddhist, preaches Puranic Hinduism in the influence of Saivite saints. Thereafter, the Pallavas used Dravidian architecture to build some of the most important Hindu temples and academies of South India. Shaivism, Shakthism and Vaishnavism emerge as the major religions of South India by the end of Kalabhara rule.

Varaha Avatar rescuing Bhumi Devi (Mother Earth) – 7th – 8th Century CE, Mahabalipuram, Pallava Kings

While the length of antariya seems to grow longer and take form of sari like drape in other parts of India in this period, people living in hot and humid Dravidian lands continued to wear short and minimal clothing. The panels from group of monuments at Mahabalipuram from the 7th-8th century Pallava empire depict people in short antariya or loin cloth tied with a kayabandh, uttariya, elaborate headgears, jatta hair, and jewellery including bangles, amulets and necklaces.

GUPTA EMPIRE (240 CE – 590 CE)

The Dark Age of Dravdian history also coincides with the Golden age in Northern-Central India. Gupta kings who were orthodox Vaishnavas, funded both Buddhism and Brahminism in seek of legitimacy for their dynasty. Gupta kings built Buddhist temples and monastic universities such as those at Nalanda. Ramayana and Mahabharata also take their final shape in this era. The Bhagavad Gita successfully manages to merge both Brhamanic as well as Sarmanic traditions of Buddhists and Jains into one scripture. The growth of ritualism in Mahanya Buddhism increasingly blurred the differences between Buddhism and Brahminism. Buddha eventually emerges as an avatar of Vishnu in Vaishnavism. Ancient Brahminism gets a complete makeover under the patronage of Gupta kings. Vaishnavism and Shaivism are the most popular religion. The decline of Gupta period in 5th century AD marks the end of Ancient Indian history timeline (and commencement of Medieval period.)

Classical Sanskrit flourished under Guptas kings who supported extensive literary works in topics ranging from medicine, veterinary science, mathematics, astrology, astronomy and astrophysics. The iconic Aryabhata made extraordinary academic contributions in the Buddhist heart land, Pataliputtra. The golden age of Brahminical resurgence also meant the worst for Shudras and Outcastes as Manusmriti was strictly enforced in this period. BR Ambedkar points to this period for orchestrating the menace of untouchability.

“Cow-killing was made a mortal sin or a capital offence by the Gupta kings who were champions of Hinduism,” notes Dr Ambedkar. He quotes historian D.R. Bhandarkar, who in his Some Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture cites a copper plate inscription, dated 465 AD and belonging to Skandagupta’s reign, which equates gau-hatya, or cow-slaughter, with brahma-hatya, or the slaying of a Brahmin. This equivalence is more or less echoed in an earlier inscription of 412 AD. It was from then on cow-slaughter began to be considered a mortal sin. – Firstpost

In response to vegetarianism preached by Buddha & Mahavir, Brahmin kings take it a notch up by banning the consumption of cow meat. Kamadenu, the sacred gaumata also emerges as a significant Puranic deity. In his book, The Untouchables, Dr. BR Ambekar also writes:

There is really no necessity to enter upon any speculation as to whether beef-eating was or was not the principal reason for the rise of Untouchability. This new theory receives support from the Hindu Shastras. The Veda Vyas Smriti contains the following verse which specifies the communities which are included in the category of Antyajas and the reasons why they were so included

L.12-13 “The Charmakars (Cobbler), the Bhatta (Soldier), the Bhilla, the Rajaka (washerman), the Puskara, the Nata (actor), the Vrata, the Meda, the Chandala, the Dasa, the Svapaka, and the Kolika- these are known as Antyajas as well as others who eat cow’s flesh.”

The kings of Gupta period comprised mostly of stitched dresses which gained the importance of royalty during Kushan periods. Since Kushans were much influenced with the Western Roman Empire therefore the coats, trousers

and boots were pre dominant dresses of royal family. People continued to wear the new fashion with indigenous styles – antariya, uttariya and kayabandh.

Mens Costume, Gupta period: A-King (Ajanta, Cave XVII), B-King, making an

offering of lotus flowers to Lord Buddha (Ajanta, Cave I), C- King and Queen (Gupta gold coin), D- Prince

(Ajanta, Cave XVII), E- Minister (Ajanta), F- Chamberlain (Ajanta, Cave XVII), G- Guard (Ajanta, Cave

II), H- GUARD (Ajanta, Cave XVII), I- Foot Soldier (Ajanta, Cave XVII), J- Bikkhu (Ajanta, Cave XVI),

K- Horse Man (Ajanta, Cave XVI)

Womens costume, Gupta period: Costumes of women. A- Queen (from Gupta gold coin), B- Votary (Ajanta, Cave II), CAttendant (Ajanta, Cave I), D- Maid Servant (Ajanta, Cave XVII), E- Court Lady (Ajanta, Cave I), FPrincess (Ajanta, Cave I), G- Court Lady (Gwalior Museum), H-Female Votary (Ajanta, Cave VI), I- Maid (Ajanta, Cave XVI)

Poverty ridden lower caste communities continued to wear the basic loin cloth and antariya.

Images (Sculptures and Paintings): WIKICOMMONS

Costume Illustrations: 4to40.com

The post Influence of Caste System in Clothing – Ancient India appeared first on Purushu Arie.