A lot of social transformations take place in Gupta period (240 CE – 590 CE), and the Brahminical four-fold varna system in ancient North India assumes the following characteristics:

- Caste is hierarchical

- Caste is hereditary

- Purity of bloodline is established through marital norms (to marry within castes)

- Occupations reserved only for specific caste on virtues of birth

- Social ostracism & untouchability on basis of caste hierarchy

Chinese scholar Hieun Tsang, who visited India in 630 CE, writes that, “Brahminism dominated the country, Caste ruled the social structure and the persons following occupations like butchers, scavengers had to live outside the city”. The disintegration of Gupta kingdom leads to decentralisation of power of early-Classical Brahminism. The succeeding kingdoms of early Chalukyas, Karkota, Harsha and other Puranic kingdoms gift virgin lands as royal grants to Brahmins in returns for agrarian exploits and social status to the rulers. With royal patronage, Brahmins spread further across the Indian subcontinent and absorb several local indigenous and tribal traditions into the new Puranic religion. With expansion of Brahminical settlements, various local Dravidian communities were absorbed into the Brahminical four-fold varna system in this period, making the varna system even more complexly layered in South India than in North – for example, incorporating local groups into Brahmin community led to stratification within the Brahmins, with some Brahmins having lower social status than other Brahmin communities.

Read: Influence of Caste System in Clothing – Ancient India

Early Puranas were written in retaliation to popularity of Buddhism, with intent to reach out to the masses including tribal communities through simple story telling. Orthodox Brahmanism undergoes radical transformation under Puranic literature thereby laying foundation of what will later become mainstream modern “Hinduism”. The early Puranas like Markandeya Purana, Matsya Purana, Vayu Purana and Vishnu Purana are roughly compiled from 250 CE to 500 CE. Few other Puranas written in this era like Brahmanda Purana, Vamana Purana and Kurma Purana and Linga Purana are completed till around 850 CE – 1200 CE. There are 18 mahapuranas, 18 upapurnas, and several other Puranic compilations which narrate the interactions of Vedic gods with people and demons.

Classification of Brahminical texts, also identified as “Hindu scriptures” in modern era.

Puranic Brahminism is primarily a fusion and distortion of various Indian customs including Vedic, non-Vedic, pre-Vedic, post-Vedic and other tribal traditions. It is primarily because of the merger of differential cults that modern Hinduism often provides varying myths for a same deity with varying geography/cultures, for example: description of Sivan’s marriage (to Parvathi and Sati/Uma) is different in Thamizh texts from that of Sanskrit. Despite the merger of Dravidian deity Sivan with Vedic deity Rudra, the local South Indian myths focusing on the knowledge-bearer aspects of Sivan is continued to be preserved in Dravidian cultures (in form of Dhakshinamurthy and Nataraja among others,) whereas the Northern depictions focus more on the fierce Bolenath antics.

Evolutionary merger of Vedic deity Rudra and Dravidian deity Sivan under various Puranic and Non-Puranic religious movements.

Powered by the popularity of Puranas, Shiva goes on to assimilate other local cults by the suffixing of Isa or Isvara to the name of the local deity, for example Bhutesvara, Hatakesvara and Chandesvara. Puranic literature also introduces god Vishnu in form of animals like fish, tortoise, boar and even a humanoid-lion, as totem symbols to appease indigenous tribes and incorporate those clans into a rural pastoral society propagated through the stories of Krishna and Rama. Over a period of six hundred years, Puranic god Vishnu assimilates several local cults like Narayana, Jagannaths, and Thirumal. By 8th century Buddha is reintroduced as an avatar of Vishnu. Though Brahminical literature goes on to assimilate and distort various aborigine cultures, the indigenous local mythologies and tribal customs continued to survive in parallel in form of oral traditions, rural village cults, and worship of kula devata/kula dheiyvam.

Puranic narratives at times varied from the previous Brahminical texts itself. For example: The Valmiki Ramayana written to counter Buddhism and reestablish Brahminism in post-Mauryan Aryavarta (North India) & Madhyadesha (Central India), describes people living in South of Vindhya mountains as dangerous dark skinned demons and asuras; however in 12th century Thamizh Puranic compilation Kamba Ramayanam written to synthesise Rama’s spiritual authority in largely Shivite Dravidian lands, the narrative is different in both spiritual concepts as well as in storyline. Likewise, burning down Raavana effigies on occasion of Dusshera doesn’t find popularity in South India like in Northern counterparts. Instead Dusshera is introduced as Vijayadhashami to Dravidian audience through Puranic mythology – celebration of defeat of demon Mahishasur by goddess Durga. In modern Bengal, several mulni basi or low caste groups celebrate Hudur Durga festival, where the asura Mahisasur is worshipped instead of Durga. They observe Durga as a symbol of upper caste domination over the Dalits. Another popular Indian festival Diwali is widely celebrated to mark the return of King Rama in North India, with roots in Ramayana. However, the Dravidian celebration of Dheepavali has nothing to do with Rama and instead commemorates the death of demon Narakasura by goddess Sathyabama (or Krishna according to other Brahmin texts) – legends rooted in Vishnu Purana and Bhagawata Purana.

By Puranic era, caste hierarchy on virtues of birth was no longer just a Brahminical propaganda but was extensively used by rulers, landlords and traders to their own greed. The history of South India clearly indicates that most of the medieval origin southern royal dynasties arose from trading and pastoral groups; hence they readily supported Brahmins in return for Kshatriya legitimacy. Brahmins and kings enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship – rituals performed by the Brahmins gave Kshatriya legitimacy to the kings and the temple land grants made by kings to Brahmins elevated them in society to the level of wealthy landowners. Although the seeds of caste system in south India was sowed by migrations of Indo-Aryans and Sanskritization of the aborigine ancestral South Indians, the caste system in South India is altered by various local factors and evolves distinctly from that in North India. In South India, caste boundaries were not as strictly marked as in north India, and the only classification that remained consistent was – Brahmin caste, non-Brahmin castes and outcastes or untouchables who didn’t belong to the caste system. While Brahmins consistently enjoyed the top position in social hierarchy, the social status and classifications of non-Brahmins kept varying with various socio-political changes.

BRAHMINIZATION OF KERALA

In Sangam era, modern day Kerala region was ruled by ancient Thamizh kingdoms of Pandya, Chera and Chola. In late-Sangam age, Mayurasharma (345-365 CE) of Kadamba dynasty of Karnataka region invited Brahmins from North India to settle in Tulu Nadu and areas of Kerala. Ays who trace their lineage to Yadavas and claimed to have immigrated from Dwaraka (modern day Gujarat region) to South India with Sage Agastya, were a dominant Indo-Aryan origin power in South Kerala during the Sangam age. Indo-Aryan Kalabhra invasion marks the end of Sangam age and thereafter Kerala enters a phase of “dark ages”. Patrons of Brahminism like Chalkuyas and Pallavas also have claimed sovereignty over parts of Kerala during the dark ages. Most scholarly sources suggest that Namboothiri Brahmins, who claimed to be the descendants of the pure Rig Vedic Brahmins, migrated into Malabar coast region during the last phase of Sangam age or early Medieval period. In the Puranic work Kerala Mahatmyam, a Sanskrit text which is part of Brahmanda Purana, the genesis of Kerala is attributed to Parasurama – the sixth incarnation of Vishnu. According to Mahatmyam, Parasurama decided to give land grants to the Brahmins in repentance to human slaughter. Parasurama then claimed a new land by throwing axe (parasu) across the sea, with which a new land emerged – this land, Kerala, was given as dana (alms) to the Brahmins. According to Keralolpathi, authored in later Bhakti period, Parasurama then sent for Shudras from various countries and settled them in the land as the Adiyans and Kudiyans, or the slaves and tenants of the Brahmins. Keralolpathi also adds that that Parasurama established as many as 64 Brahmin settlements called the gramas of which 32 belong to modern day Kerala, and the other 32 which are in Tulu Nadu of modern day Karnataka. Unlike the Namboothiri Brahmins of Kerala, the Tulu Brahmins do not claim the ownership of the land. The Parasurama myth of creation of Kerala contradicts the Puranic legend of Dasavatharam where Vamana avatar (5th incarnation of Vishnu) predates the Parasurama avatar (6th incarnation of Vishnu). According to Puranic mythology, asura king Mahabali who ruled Kerala, failed to fulfil promise to provide land to Vamana and therefore bows down and submits to Vamana – the dwarf Brahmin. Traditionally, Malayalees celebrate Onam to commemorate the Dravidian King Mahabali. While some Malayali Dalit communities observe Onam as a black day since it symbolises Brahminical hegemony over the aborigine people of the region, few Brahminical groups proposed the day as Vamana Jayanthi to commemorate Vamana instead of Mahabali. The Parasurama’s creation of Kerala or Mahabali’s encounter with Vamana, can be viewed among the many other inconsistent Puranic Brahmin myths propagated to assert Brahminical supremacy and legitimacy of land holding rights in places where Brahmins migrated to. It is theorised that Kotravai, the mother goddess of ancient Cheras was assimilated into the present-day form of the goddess Durga in this period of Sanskritisation. Although the Brahmin settlements in Kerala begins in late Sangam era, significant Sanskritisation or Brahminisation of Malayali society begins after 8th century with the rise of Bhakti movement and socio-political conditions in war trodden kingdom of medieval Cheras.

PALLAVA DYNASTY (275 CE–897 CE)

Early Pallava dynasty gain prominence around 275 CE after the fall of the Satavahana dynasty. Pallavas are possibly Deccan aborigine pastorals who later served as feudatories of Satavahana rulers. Much like Satvahanas who adopted orthodox Brahmin religion, Pallava kings identified themselves as descents of Brahmin Ashwattama, assumed Bharadwaja gotra, and established Indo-Aryan model of kingship in medieval South India. Other theories suggest Pallavas were descendants of North Indian dynasties who moved southwards and adopted local traditions to their own use. Invasion of Indo-Aryan Kalabhra rulers leads to the eclipse of early Pallavan stronghold. Pallava king Simhavishnu dethrones Kalabhra rulers around 575 CE, and establishes medieval Pallava Empire in modern day Kanchipuram by 600 CE. His son Mahendravarman I and grandson Narasimhavarman I preach Shaivism and patronage the extraordinary group of monuments in Mahabalipuram. Narasimhavarman’s general Paranjothi was renowned for his devotion to Shiva and was one among the 63 Nayanars of Bhakti movement. The Pallava rule marks the rise of Bhakti movement and thereafter, Thamizh Nadu emerges as one of the most significant bastion for Brahminical patronage in Medieval India. This period sees a major influx of Brahmins from North India to South, as they were generously granted lands and gifts by Pallava rulers.

Early medieval kingdoms after the disintegration of Gupta and Satvahana empires.

Ashwamedha yajna and other Vedic rituals, as well as the first Sanskrit language inscriptions of Thamizh Nadu in Grantha script is introduced to South India in Pallava period. Arya-Dravida socio-cultural synthesis hits an unprecedented high in this period as Pallava kings go on to build some of the most important Puranic temples and academies of medieval South India. Pallava kings popularised the practice of dedicating temples to different deities – most of the arising Thamizh origin Puranic mythologies are very closely tied to these shrines and the local gods they’re dedicated to. Exclusive Brahminical colonies known as agraharams emerge around the temples in this era. The immensely wealthy Dravidian temples were now directly controlled by the Brahmins who were no longer just priests but adopted new professional roles as financiers and traded in commodities, and these iconic Pallavan temples emerged as the citadels of orthodox Brahminical caste system. While the immigrant Indo-Aryan customs did not at first have supreme social powers in medieval Thamizh Nadu, their spiritual authority grows over time and Brahminical four-fold Varna system becomes an integral part of Dravidian society under the Pallavan rule. Earliest mentions of untouchability and slavery in South India are found in verses of Shivite Nayanar poems of Thevaram and Vaishnavite Alvar poems of Divya Prabhandam. Initially, untouchability in South India was mostly in relation to entry into temples; however untouchability extends to other social aspects in the period of Imperial Cholas in 11th and 12th century CE.

Varaha Avatar rescuing Bhumi Devi (Mother Earth) – 7th – 8th Century CE, Mahabalipuram, Pallava Kings. While the length of antariya grew longer and takes form of sari like drape in other parts of India by early Medieval period, people living in Dravidian kingdoms continued to wear minimal short clothes. The panels from group of monuments at Mahabalipuram from the 7th-8th century Pallava empire depict people in short loin cloth (kiludai) tied with a waist band, meladai, elaborate headgears, garlands, and extensive jewellery.

Pallava king Simhavishnu with his two queens.

The Satvahana influences in Pallavan costumes are evident in the breast-band of central India which finds its way into medieval Thamizh Nadu – known as Vambu, Vaar or Kachchu in Thamizh. Breast bands of some female figurines even feature halters. The male royal figurines of Pallavan era also depict 2-piece clothing sirradai (loin cloth draped on lower body) and meladai (draped on upper body). The lower garments worn in Pallava period in some cases appears longer than that worn by the royals in ancient Sangam era. The upper body drape of men corresponds to the present day angavastram clothing of modern day Pancha-Dravida Brahmins.

The single piece of garment draped over both upper & lower body – sari, which gains prominence during Kushan rule in North India, finds no reference in either of Pallavan arts or the Sangam works. It is also noteworthy that from the Mauryan sculptures of Sanchi and Barhut to the Satvahana arts of Amaravati and Ajanta, it is only women who are decked with anklets. This clothing trend is observed in early Pallava arts; however Pallavan arts of Rajasimhan at Kailasanatha temple, Kanchi and the Shore temple depict even men wearing leg ornaments.

Costumes & Jewellery of Pallava Kingdom, Image: Dr. Gift Siromoney, MCC Magazine, Vol. 39, April 1970

Costumes & Jewellery of Pallava Kingdom, Image: Dr. Gift Siromoney, MCC Magazine, Vol. 39, April 1970

FACIAL HAIR – Warriors sported moustache, rishis pointed beards, but kings and gods are clean-shaven.

MAKEUP – Men and women applied three colours to their body – sandal-wood paste, chunnam and red kunkum, and eye-lids with anjanam.

HEADGEARS & CROWNS – Krita Makuta is a tall cylindrical crown, mostly worn by Vishnu and royal figurines. Jata Makuta is a distinctive hair-style resembling the crown depicted on Sivan. Karanda makuta is the most popularly worn headgear by common men and women in the form of a cone with tassels and other decorations.

GARLANDS – Aathondai flower (Capparis zeylanica) was used by the Pallava kings for garlands. Nandikalambakam also refers to garlands being worn on crown. However, the flowers in the stone sculptures of Pallavan arts aren’t depicted with the same clarity as in the bronze figurines of succeeding Chola period.

NECKLACE – Necklaces were of gold and precious stones and often worn without pendants by both men and women. Pendants (thooku) were worn by females. Veera sangili or Swarnakshaka refers to pearl-strings which go over both shoulders and are tied in the middle, forming an ‘ X ‘ in the front and back. Yagnopavita denotes a variety of ornaments which are worn over the left shoulder. Yagnopavita of different kinds with clasps, long ones going down to the leg, double and triple strands meeting at the clasp are found in Pallavan figurines at Mahabalipuram.

BELTS & WAISTBANDS – A men’s ornamental belt called the udhara bhanda is worn just above the stomach. A waist belt (arai naan or kati sutra) knotted in front with a bow is worn by people of every genders.

EARRINGS – Ear-ornaments were a big trend for Pallavan people. In the ears they wore makara kundala (makara kuzhai in Thamizh) shaped like a fish or a crocodile, and patra kundala (thodu or olai in Thamizh) a circular ornament which was inserted in the lobes. Precious stones and gold were used to make the ear-ornaments, but it was also common to use palm leaf, clay and shell for making the different kinds of patra kundala. Women appear with the makara kundala on the left ear and patra kundala on the right and vice versa.

ARM BANDS & BANGLES – In the Pallava period the bangles were made not only in gold (thodi) but also from sea-shells (valai). A simple circular band worn on upper arm is called thol valai. The second kind is a cork-screw-shaped ornament which goes round the arm twice or thrice and is the most common arm-band in Mahabalipuram. The third is an elaborate ornament called thekeyura which is set with gems, and some of these keyuras have extraordinary cross-like pattern around a circle.

ANKLETS – Hollow anklets (silambu) worn by women were made of gold with loose pearls inside to produce a characteristic sound. Nandikalambakkam mentions the kazhal, a leg ornament worn by king Nandivarman.

Rings on fingers and toes as well as nose-rings are not depicted in Pallavan arts and neither are any ornaments on thighs.

EARLY CHALUKYAS (543 CE – 753 CE)

The Brahminical migrations to Telangana, Andhra, Goa and Karnataka dates to 600 BCE – 400 BCE. Satavahanas who initially ruled modern day Maharashtra-Goa region and later controlled Telangana, Andhra and Karnataka were the earliest Deccan dynasties to be Brahminized. The Satavahana rule in Karnataka was succeeded by Kadambas who were Havyaka Brahmins and adopted Vedic Brahminism. Early Chalukyas were initially subordinates to Kadambas and Pulakeshin I establishes the first soverign Chalukya dynasty in 543 CE. Origins of Chalukyas is subject to varying opinions. The early Chalukyas address themselves as descendants of the Brahmin Kadamba rulers in their inscriptions. Few theories suggest Chalukyas were descendent of Andhra Ikshvakus. Brahminical literature, such as the Ramayana and the Puranas, connect the Ikshvaku’s lineage to Ayodhya of the Kosala Kingdom in northern India. A later record of Eastern Chalukyas credit Chalukya lineage to a ruler of Ayodhya who came south, defeated the Pallavas and married a Pallava princess. Several historians hold the view that an earlier southern migration is a distinct possibility and their subsequent Kannadiga identity may have been due to their success as chieftains and kings in Karnataka region. The reign of the Chalukyas saw the arrival of Kannada as the predominant language of inscriptions along with Sanskrit, in southern peninsula outside the Tamizhakam (Thamizh country). The early Chalukya empire reaches its zenith under Pulakeshin II who conquered most of Deccan plateau and pushed forth up to the Narmada, where he came face to face with Harshavardhana of Kanauj. The last Chalukya ruler, Kirtivarman II, was overthrown by Dantidurga of Rashtrakuta dynasty in 753.

Costumes of medieval Karnataka – Illustrated depiction of Chalukya king Pulakesin II receiving envoys from Persia. Costumes of Chalukya ruled Karnataka corresponds with the costumes worn by their arch-rivals Pallavas. The illustration depicts king Pulakeshin II wearing short lower garment drape, headgear, armband, bracelets, earrings and necklace. Illustration also depicts women’s breast covering which reached the region with Satavahana rulers.

Artist’s depiction of the defeat of Chalukya king Pulikesin II by Mahamalla Narasimhavarman Pallava at Badami.

Costumes and jewellery at Cave temple of Badami, 578 CE in the rein of Kirtivarma I of Chalukya dynasty.

BHAKTI MOVEMENT (7th century CE)

The Bhakti movement originated in 7th century CE in Thamizh Nadu at a time when Brahminical religious customs had to compete the popularity of Buddhism and Jainism in South India. The Bhakti movement promoted devotion among masses regardless of socio-economical identities. While most Bhakti poets, Shaiva Alwars & Vaishnava Nayanars, belonged to Brahmin & Arasar (ruler) class, the movement also included poets of other communities like Vanigars, Vellalas, Idaiyars, Kuyavar, Panar, Vedar, Sanar, Saliyar, Sekkar, and Vannar. While caste itself isn’t the central theme of Bhakti movement, its sincere devotion to god regardless of caste identity gains acceptance from a wide range of communities, and later reaches northwards through Karnataka and Maharashtra, and reaches its zenith in 15th century Bengal and northern India. The “surrender-to-God” approach of Bhakti movement later influences devotional practices in Islam such as Sufism and majorly revolutionised another medieval Indian religion – Sikhism.

Kannappa Nayanar, a non-Brahmin born in Vyadha (hunter) family was one of the 63 Nayanars or holy Saivite saints mentioned in Sundarar’s 8th century Bhakti movement poems. The figurine depicts Kannappa in beard and moustache, wearing popular Pallavan era attire: short sirradai (lower garment), waistband, veera sangili maalai (across chest), thodi (bangles), thol valai (arm band), thodu (earrings) and footwear.

Thiruthondar Thogai, an 8th century compilation of list of Saiva sect Nayanars who spearheaded the Bhakti movement, makes a one-line reference to Nandhanar (also known as Thirunaalaippovar,) as one of the Nayanars who was longing to enter the temple. Though the texts does not explain what hurdles he had to face in entering the temple, by 11th cenutry AD, another Thamizh Saivite text Thiruthondar Thiruvanthathi states that Thirunaalaippovar was a Pulaiyar, a lower caste by birth, who sought access to the Shivaloganadar temple in Tiruppungur and the Nataraja temple in Chidambaram. As the threat to popularity of Brahminical philosophies from Buddhism reduced substantially under the state patronage of Pallavas and medeival Cholas, the caste-based social order regains its importance in Puranas as observed in 12th century account of Nandhanar in Periya Puranam. The Periya Purana of 12th century CE goes on to appropriate & assimilate the protest of Nandhanar by adding that he gains access to temple worship only after his caste-oppressed Pulaiya body is ‘purified’ by the sacrificial fire, and he reappeared like a Brahmin sage, wearing matted hair (characteristic of a Shaiva) and the sacred thread worn by Brahmins across his chest. The Puranic version is interpreted as a classic Brahmanical supremacist propaganda, where a particular lower caste individual is granted salvation by transforming into a Brahmin; where the superiority of the Brahmins is reinforced and the ban of Pulaiyars in temple is not challenged.

1942 poster of Thamizh film – Nandhanar

MEDIEVAL CHERAS (800 CE -1102 CE)

Cheras reestablish their political authority in Kerala region under the leadership of Kulasekhara Varman by 9th century CE. All the kings of second Chera empire adopted the official title Kulasekhara Perumal, originating from the founder of the dynasty. Hence, the second Cheras are also known as Kulashekaras or Perumals. The revival of Chera power between 9th and 10th centuries is remarked as the golden period of Kerala history. Kulashekara kings were great patrons of the arts, literature and science. Under the patronage of Perumals, Kerala even gets its own distinct writing script – Manipravalam, which was used to write an admixture of Proto Thamizh-Malayalam language and Classical Sanskrit. Several religion including Jainism, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and Puranic Brahminism co-existed peacefully in Kulashekaras kingdom. The medieval Chera Empire was divided into provinces under the rule of Nair Chieftains, with each province comprising a number of Dhesams under the control of local chieftains. There were two kinds of chieftainships: hereditary – like the governors of Kollanatu, Venatu, Eralanatu, and Valluvanatu; and nominated like the chieftains of Ramavajanatu, Nanrulainatu and Netumpuraiyumatu.

Chera kingdom, chieftaincies, and Chola mandalams c. 11th century

Though the medieval Cheras enjoyed lordship over a number of independent chiefs in the locality, they didn’t wield complete control over Kerala region as a centralised kingdom. By 8th century, Brahmin settlements controlled vast estates of land in the fertile river valleys. These settlements were significant in controlling the power of medieval Chera throne. A council of Brahmins called Nalu Tali, a junior prince called Koyil Adhikarikal and bodyguards known as Ayiram (thousand) were closely associated with power control of Perumals. The new social equations powered the monumental rise of Namboothiri Brahmins and Puranic religion in medieval Kerala. With the rising political authority of priests, the Namboothiris were at the top of medieval Kerala’s caste hierarchy, outranking even the kings. The prolonged series of wars with the Cholas led to significant weakening of the Chera ruler’s control over their territories. Several local Chieftains used the political instability to assert their independent rule. The disintegration of the Perumal suzerainty resulted in the emergence of Venatu, Kozhikotu and Kolattunatu as independent kingdoms. In coming years, Namboothiri Brahmins of Kerala go on to interpret Manusmriti according to their whims and wills, resulting in one of the most complex and worst case of apartheid caste system prevalent in Indian subcontinent.

Illustrated depiction of costumes of Namboothiri Brahmin

Mundu, a plain white rectangular cloth wrapped around the waist was the most common attire of worn by every gender in medieval Kerala. This plain white dress was worn by all, regardless of their caste, however Namboothiri Brahmins and rulers distinguished themselves in mundu with kasavu zari. Long traditional mundu were twisted and used as Uthareeyams in the form of a large Yajnopaveetham by Namboothiri men. Namboothiri males also wore Kapunim tied round the waist, passed between the thighs and tucked in at the front and back, with pleated front. The melmundu was a fabric worn over shoulders and also indicated caste status. For example, in presence of an upper caste person, the lower caste men should keep their melmundu either around waist and tucked under armpits. The upper caste sections wore rich silks and very fine semi transparent cotton clothes. Namboothiri men also wore wooden sandals called methiyyadi. Sporting a Kaduma, a tuft of lock of hair which was knotted and kept in different styles, was mandatory for Namboothirs. Kaduma was popular even among other social sections including the Malabar Christians.

Methiyyadi features a mushroom-shaped knob in front on a wooden.

The Namboothiri women wore Pudava around the waist usually measuring up to 7 feet in length and 2 feet in breadth. The Pudava was also draped in Kapunim style. The practice of covering the upper body didn’t gain prominence in Kerala till the influx of Christianity and Islam. Women wore mulakacha, a fitted bodice which was knotted from behind. By late medieval period, it was trendy for upper caste women to wear Neriyathum, a shawl like garment draped around the torso. This act of wearing clothes on the upper body was illegal for the lower caste women and was interpreted with disrespect towards the upper caste. Nair men and women wore a mundu and did not cover their chest. Nair women adorned themselves with ornaments and flowers. Widows however were prohibited from wearing ornaments.

Andal – the only female among the 12 Alvar saints featured hairstyle and jewellery which are unique to early medieval Kerala.

Illustrated portrayal of royal costumes of 17th century Kerala. The image depicts Johan Nieuhof’s audience with the Queen of Quilon (Kollam).

Illustrated depiction of a Malabar man and woman, around 1680 CE. Image: Dutch by the trade diplomat Johan Nieuhof

Women belonging to lower caste communities mostly wore Ottamundu – a short piece of cloth which was draped on the lower body. Thorthu was wrapped and tied around their waist commonly by people from lower caste communities. Agriculture labourers also wore Thoruthu as Thalekettu (turban). Ezhavas, Pulayas and Parayans wore a short loin cloth called Konakam. Other lower caste comunnities like Thanta Pulaya and Nayadi continued to wear leaves and vegetation as garments.

ADI SHANKARA’S ADVAITA VEDANTA (8TH CENTURY)

Adi Shankara, a Namboothiri Brahmin from present day Kerala region criticised the superstitious beliefs of ritual centric Brahminism. Shankara observed that the masses could not be kept interested in the religion without the power of the prayers. Shankara enabled the integration of the ongoing Bhakti movement with orthodox Vedic Brahminism stating that they were two sides of the same coin. Adi Shankara even identified the merits of Buddha’s teachings and incorporated them with Smartha traditions. It can also be commented that Adi Shankara emerged as the most important figure in wiping out Buddhism from India and reviving the authority of Brahminical literature. Although Shankara advocated harmony of castes, he wasn’t against caste system itself. Instead Shankaracharya protected and propagated Brahminical caste system. Adi Shankara interpreted Brahminical texts in such a way which would give lower-caste the right to know itihasa (Ramayana & Mahabharat) and Puranas, which in turn powered the popularity of Puranic Brahminism but denied them the knowledge of Vedas which were strictly confined within upper-caste sections.

In the book “Riddles in Hinduism”, Dr. B R Ambedkar points out the irony where Adi Shankara’s Vedanta contradicts his own preaching of casteism.

“Why then Vedanta failed to produce a new society? This is a great riddle. It is not that the Brahmins did not recognize the doctrine of Vedanta. They did. But they did not ask how they could support inequality between the Brahmin and the Shudra, between man and woman, between casteman and outcaste? The result is that we have on the one hand the most democratic principle of Vedanta and on the other hand a society infested with castes, subcastes, outcastes, primitive tribes and criminal tribes. Can there be a greater dilemma than this? What is more ridiculous is the teaching of the Great Shankaracharya. For it was this Shankarcharya who taught that there is Brahman; this Brahman is real; that it pervades all; And at the same time upheld all the inequities of the Brahminic society. Only a lunatic could be happy with being the profounder of two such contradictions. Truly as the Brahmin is like a cow, he can eat anything and everything as the cow does and still remain a Brahmin.”

– Dr. B. R Ambedkar

Both the Bhakti movement and Advaita Vedanta failed to annihilate discrimination on basis of caste. In contrast, the omnipresence of caste in medieval Indian society became such that by 8th century CE, varna and jati find acceptance even in Jain literature. Several non-Brahmin communities who enjoyed economical status appropriated the popularity of Puranic Brahminism to their own benefits with myths associating their heritage and lineage to various Puranic gods who were popular at the time. The caste system in South India only grew more rigid and complex with the spiritual authority of Bhakti movement and Advaita Vedanta. For the first time in history, South Indian society fully vexed with strict untouchability and other complex casteist norms.

RASHTRAKUTAS (753 CE – 982 CE)

The early Chaluyas of Badami were succeeded by Rashtrakutas in 753 CE. The origin of the Rashtrakuta dynasty again is subject to many controversies with possibilities suggesting north western ethnic groups, tribes of Punjab, Maratha origin, Andhra Reddys, and native Kannadiga ancestry itself. Rashtrakutas supported the spirit of religious tolerance and were patrons of Jainism, Shaivism, Vaishnavism, and Shakthi faiths. They also supported Buddhism, although the religion declined significantly by this time with spread of Adi Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta in South India. Even the Buddhists and Jains who originally disregarded caste system, adopted it with the rampant prevalence of Brahminical social order in South India. Besides the four traditional castes, inscriptions from medieval Karnataka speak of up to 18 castes and sub-castes. Among the 18 caste divisions, Brahmins enjoyed the supreme status and most of other castes in Karnataka were primarily tribes who were assigned caste identities by the local Brahmins and rulers. Brahmins increasingly practised non-Brahminical professions such as agriculture, trade and in army. Gavera, Gatriga, Setti, Settigutta, Ankakaras, Gandiga, Gauvnda are few Vaishya classification mentioned in the inscriptions. Other caste divisions in medieval Karnataka include: Panchalas (smits, sculptors and carpenters), Agasa (washermen), Navida (barber), Kumbhar (potter), Mochchiga (cobbler), Meda (basket maker), Golla (gowherd), Uppara (mason) etc. Zakaya or Lahud caste consisted of communities specialising in dance and acrobatics. Capital punishment, although widespread, was not given to the Kshatriya sub-castes or to Brahmins. In Rashtrakuta Empire, inter-caste marriages was common among lower caste communities, whereas the upper caste community avoided nuptials outside their caste divisions. Inter-caste socialisation was discouraged and dining together between people of various castes was avoided. Untouchability takes shape in Karnataka during Rashtrakuta and succeeding Western Chalukya rule. Saniagara, Chandala, Holeya, Madiga, Naviga were considered lowest castes in the society. They usually resided in the outskirts of the village or town and had their own deities and temples. While Shudras are rarely mentioned in the preceding rule of early Chalukyas, Antyajas – lower caste sections who consumed cow meat were involved in various menial services. Alberuni who visited India during 1007 to 1033 CE, states that “After the Shudra follow the people called Antyaja, who are not reckoned amongst any castes. There are eight classes of them, who freely intermarry with each other, except the fuller, shoemaker, and weaver, for no others would condescend to have anything to do with them. These eight guilds are the fuller, shoemaker, juggler, the basket and shield-maker, the sailor, fisherman, the hunter of wild animals and of birds, and the weaver.”

Costume illustration of Kailasa stambha and other artworks from the Kailashnath Temple Kailash Temple at Ellora Caves

Costume illustration showing Kama and Rati at Kailasha temple Ellora Cave 16

Costumes and jewellery at Mallikarjuna temple, Pattadakal dating to 7th-9th centuries CE, sponsored by the Chalukya and Rashtrakuta dynasties.

The costumes of Rashtrakutas continued to follow the trends of Pallavas and early Chalukyas. However inscriptions from the period suggest that only upper-caste people could wear turbans, and the practice trickled down to the lower caste sections much later in the region.

MEDIEVAL CHOLAS (848 CE–1279 CE)

Raja Raja Chola I of Chola dynasty establishes one of the mightiest empires of India controlling the areas stretching from Sri Lanka in the south to Kalinga in the north. Medieval Cholas claimed chakravartin legitimacy, adopted the Brahminical social order of preceding Pallavas, and employed Brahmins as their priests. Aided by Bhakti movement’s influence, Brahmins gained supreme status in social and religious spheres of medieval Chola kingdom. Even the accession of a king to the throne had to be legitimatised by the Brahmin priests in the days of medieval Cholas. Caste regulations in respect of temple entry became more rigorous. Untouchability and unapproachability became rampant. The number of sub-castes multiplied. While Thamizh gains the status of global language under the Chola kings, they simultaneously promoted the learning of Vedas and Sanskrit. First Thamizh version of Ramayana is compiled by Kambar in this period. The Brahmin community of the Chola country not only consisted of local Thamizh Brahmins but also Brahmins from Malayala region, Brahmins from Kasmiradesa, Aryan Brahmins from Gowdedesa, and Brahmanasa from Uttararastra of Uttara-patha. They received variety of gift from the rulers, in the form of tax-free lands, gold, money and other moveable assets. In Chola kingdom, Brahmins not only served their traditional roles of priests but also assumed the roles of ministers, commanders, councillors and local administrators.

Chola Empire & territories in 1030 CE. Medieval Chola kings excelled in administration, revenue models, tax collection, and also built a massive naval fleet.

Brahminization of Thamizhakam reached its peak during the period of imperial Cholas and this led to a form of slavery, mainly associated with land ownership. With the distribution of tax-free lands as gift to Brahmins by the kings during the Pallava and Chola periods, Brahmins, who were until then mostly advisers and purohits to the king, became landowners in several places. While the Pallava and Chola kings boosted Brahmins with the status of landlords, several indigenous Adi-Dravidian communities like Paraiyar and Pallars were alienated from their own lands under the new casteist social order.

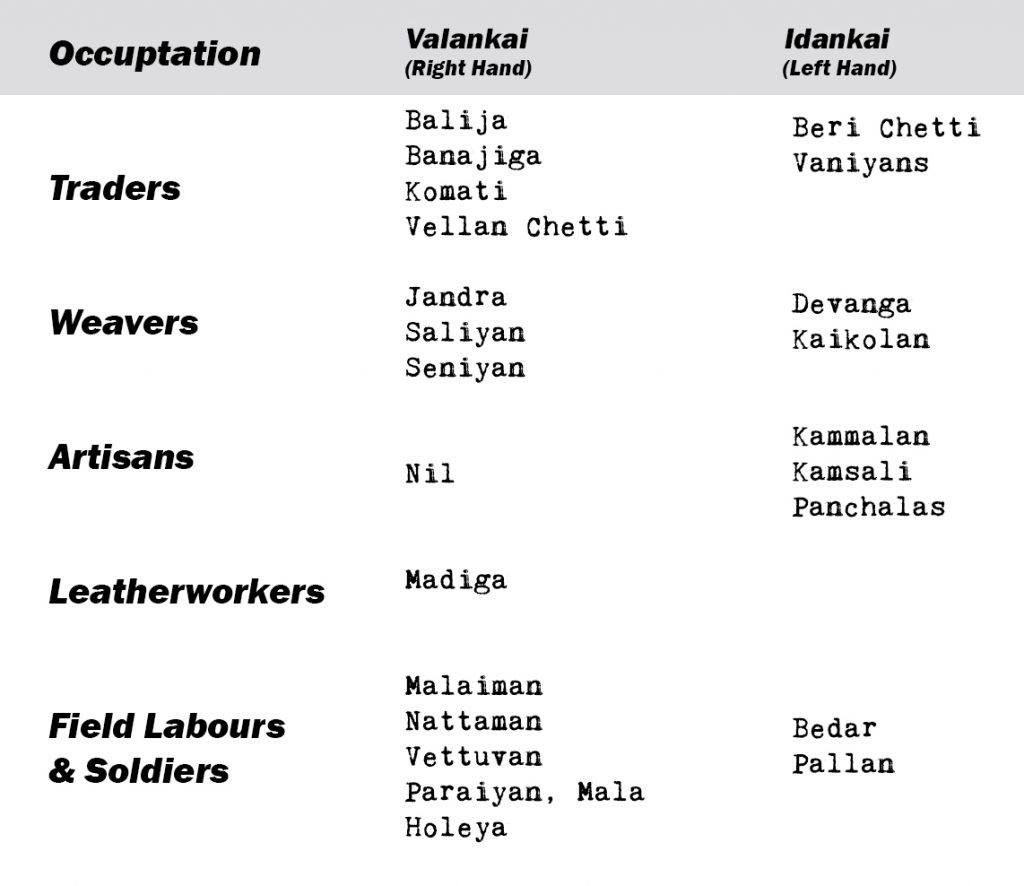

Caste divisions in medieval Chola dynasty was also classified as Idankai and Valankai (in Thamizh) or Edagai and Balagai (in Kannada), translating to left arm and right arm respectively. Several texts of this era refer to troubled relations between the right-hand and the left-hand factions. The genesis of the division into right hand and left hand castes is one of the riddles of south Indian history. Ninety eight sects under each of the two divisions were generally of the industrial and agricultural classes. The Brahmins, ruling class and a few other communities who claimed the highest social status were kept aloof from these two classifications.

Classification of castes under Valankai & Idankai divisions in medieval Chola kingdom.

Vellalas, a dominant caste of land-owners occupied the first place in the social scale among the non-Brahmins in medieval Chola kingdom. They called themselves Pillai, Chettiar, and Mudaliar. While earlier Thamizh texts classify Vellalas as cultivators & non-cultivators, several new sub-castes emerge among Vellalas as they assume new roles and contribute to the royal and military services of Cholas. Vanigar is another caste division that’s primarily associated with trade. The word Vaniyam signifies trade in oil and its production. Though the oil-traders held low status in the social scale, they provided significant service in lighting the temples – a major consumer of oil products in Chola country, and thereafter are believed to have earned their high social status. Vanniyars are the only Thamizh origin caste to have their own Puranic compilation – Vanniyar Puranam. Paraiyar, derived from the root word Parai which means a drum, denoted the caste of drummers. Some of them also served as bonded agricultural labours, domestic servants, gravediggers, watchmen, scavengers, hunters, soldiers and potters. Paraiyars claimed to be the descendants of Ravana who resisted the Aryan cultural invasion in South India. Paraiyar division also included Valluva – priests who performed the funeral obsequies in the royal household before the rise of Brahmin power in South India. By medieval Chola period, Valluvas abstained from beef eating – a dietary habit continued by the other Pariyars. Some of the other popularly mentioned caste divisions in Chola inscriptions include: Chakkiliyar (cobblers), Chetti (merchants), Ahambadiyar (land owners), Muttaraiyar (army generals), Ambattan (Barbers), Pallar (agriculture labours), Kammala (artisans), Thattan (gold smiths), Kollan (black smiths), Thacchan (carpenters), Karuman (stone masons), Visvakarma (metal smiths) and Kaikkolars (weavers).

Aided by flourishing trade and pan-continental influence, the weaving community (Kaikkolar) of Chola kingdom produced various types of clothes for the requirements of the temples, royal households and also for common people. Padaliputram (Poddaalapura), Chirapalli, Nagapatnam, Cholapatnam and Thondaimandalam were important centres of textile production. Pumpattu, Pachchilai pattu, Konkala pattu, Pulivur pattu, Patola pattu and Venpattu were different types of silk produced in this period. Fabrics woven with gold threads for auspicious occasions were called ponnadai. While silks mostly adorned the royals, cotton weaves remained popular among the commoners as pointed out by 13th century Chinese writer named Chau-Ju-Jua. Sella (Muslin) and Vichithra (Chintz) were the other mainly woven fabrics in this period.

Granite sculpture of Brahmini wearing kachhu (breast band) with halters, lower garment reaching mid-calf length, thodu (bangles), silambu (anklets) and paampusurul (arm band) – Chola Kingdom, 11th Century.

Periya Puranam accounts that women wore attractive cottons and silks. Tugil aruvai, tuni, tundu, were the

names of the cotton cloth, whereas silk cloth was referred as Pattadai, Ponnaram, Uttarivam, and Manikilaradai. Tugil and Kalingam were perhaps imported clothes. Tugil seems to have been fine in texture and worn in summer season. Kalingam was a dyed cloth and black in colour. Young women wore red silks upon attaining puberty.

King Rajaraja Chola and guru Karuvur Thevar, Brihadeesvara temple, Thamizh Nadu, 11th century. This is the earliest known royal portrait in Indian painting. This may not be an exact rendering of the king’s features, rather a stylised representation.

The changes from Pallavan clothing to Chola clothing appear more evolutionary than revolutionary in nature. Emergence of pudavai, a predecessor of contemporary sari, can be noted as the most significant change in the silhouettes of Chola costumes from that of Pallavas. Earliest pudavai is worn around the waist with the chest bared. 10th century text Seevaga Sinthamani states that pudavai was folded with pleats in front. The length of earliest pudavai is unknown. Surrupudavai and Niravadi pudavai are the two variations of the costume in the reign of Kulottunga Chola (1070-1122 AD). Niravadi pudavai is three-yards in length. Cotton pudavais were referred to Parutti Pudavai. A 11th century inscription refers to the presence of tailors in medieval Thanjavur. The tailors stitched kachchu (breast-covering) which was intricately embellished and decorative. Kiludai (lower garment) and meladai (upper drape) remained the primary garments worn by every gender. Unlike the short lower garments worn in Pallava period, the Chola figurines consistently feature kiludai reaching the calf length or ankles. Women also wore Kachchu (breast covering) which was mostly popular among the urban dwellers and royals. Long & stretched ear-lobes piercing was in fashion.

Queen Sembiyan Mahadevi 10th century CE Chola Empire. The figurine is wearing Karanda makuta (crown), Yagnopavita (across chest), Mekalai (girdle), ankle-length Pudavai, Paampusurul (arm band with a cobra head), Valai (bangles), and Kolusu (anklet). The figurine also depicts long & stretched ear holes.

Most aspects of the Pallavan jewellery are continued to be worn in Chola period. Most of these ornaments were worn by people of every sex. The mekalai (girdle) worn by Chola figures are far more elaborate and detailed than Pallavas. Chola figurines also feature necklaces that are worn closer to the neck than in Pallava figurines. Heavy lockets encrusted with precious stones like ruby and emerald was particularly worn by the royals. Pearl fishing was an important aspect of Chola trade and pearl ornaments were popularly worn in this period. Pearl necklace usually with 7, 5, or 3 strands was called Saptasari, Panchasari or Trisari respectively. Ekevalli is a single strand bejewelled chain made out of pearls, corals, lapis lazuli and sapphires. Udhrabandha was a waist band or belly used round the torso above the naval but below the breasts. Chudamani is a head ornament worn at the parting of the hair in the centre of head. Chuttu is a disc-like or circular shaped ornament, suspended from the parting of the hair by means of a small chain usually laid on the parting line on the head. Chuttu was worn by women of all classes including princess, court attendants and temple dancing girls. Thodu (earrings) came in several shapes including circular-ring, circular disc, spiral, fish shape and large gem stone encrusted. Nose ornaments (absent in Pallava art) emerges as a big trend for every sexes as indicated in the Inscriptions from Thanjavur during the reign of Devaraya II. Valayal (bangle) made of gold was known as Katakam. The arm band worn in Chola period, known as paampusural features a cobra head at the upper end. Modhiram translates to ring worn on the fingers and the toe ring was called Thirukkal modhiram; the latter was particularly popular among married women. Married women also wore Thali, a pendant worn by married ladies as a sacred symbol of their being married women. Thilakam or pottu (bindhi) was worn on forehead by both married and unmarried women. Young girls popularly styled their hair in two or more plaits possibly even five. Married women were more likely to tie their hair in coiffure or Kondai in Thamizh. In Chola era, art of preparation and use of cosmetics was one among the 64 arts and women of this period used make-up box (Toilet Box) which comprised pastes, washes and unguents. Natural perfumes and different kinds of herbal juice were used to decorate their hands, feet, fingers and toes. Collyrium was applied to eyelids and eyebrows with the brush called kol. People of medieval Chola kingdom also applied sandal and turmeric paste on their bodies – a tradition that has origin in post Sangam period and it continues to be in use even to-day.

Chola Fresco of Dancing girls, Brihadisvara Temple, Thanjavur, 1100 CE

In the Chola period, there are references to dancing girls known as Devar Adigalar or Devadasi who were bought for temples. Dancing girls usually wore a kiludai (lower garment) and araikkachchu was worn at the hip.

The outcastes or untouchables and tribal people in medieval Chola period wore animal skins, dried leaves, and peacock feathers as clothes.

WESTERN CHALUKYAS (973 CE – 1189 CE)

Taliapa II, a descent of the earlier Chalukyas of Vatapi, overpowers the Rashtrakutas to establish Western Chalukya Empire. Western Chalukyas exert control over Karnataka, Maharashtra, parts of Southern Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, Telangana and Western Andhra. Western Chalukyas were in constant battle with Cholas over the control of fertile Vengi region of Andhra. Fall of Rashtrakutas coinciding with the defeat of Western Ganga Dynasty to Cholas who patronaged Puranic Brahminism, leads to the fall in popularity of Jainism in South India. Under the influence of saint Basavanna, a new religious movement emerges in Karnataka – Veerashaivim or later known as Lingayatism. Lingayatism has roots in Thamizh Nayanar Shaivism and emphasised personal religious experience over text-based dogmatism. Basavanna was an influential Lingayat figure who promoted personalised direct worship of Shiva and rejected ritual-centric worship and casteist norms of Brahminical literature. By later medieval period and up to 21st century, several Lingayats campaigned for recognition of Lingayatism as a separate religion, arguing that Lingayatism rejects the social discrimination propagated by “Hinduism” – a modern term used to collectively denote Vedic, Puranic and other local Indian cults assimilated by Brahminism.

A necklace with pendant containing linga symbol of Shiva are worn by Lingayats. Rudraksha beads and Vibhuti (sacred ash on forehead) are other symbols adopted as a constant reminder of one’s principles of faith.

The rise of Veerashaivaism was instrumental in challenging the Brahminical caste system which however continued to prevail with royal support of Western Chalukyas. Brahmins continued to enjoy their status as providers of knowledge and justice, and served as ministers and administrators who formulated social rules by functioning as neutral arbiters through Panchayats. Much like in preceding Rashtrakuta rule, Brahmins enjoyed various royal grants. Corresponding to the social norms in Chola kingdom, Brahmins of medieval Karnataka lived in agraharas built around the temples. Schools and hospitals were built in the vicinity of these agraharas and kept away from the reach of lower caste sections. Kshatriya was a loose classification legitimised by Brahmins to rulers and chieftains. In religious field, the Kshatriyas were the only other caste allowed to study the vedas in medieval Karnataka. By this period kings considered it their duty to protect caste rules. Kings labelled themselves as protectors of Varnashrama Dharma. Vaishya was again a loose term since Brahmins exercised significant hegemony on trade. The non-Brahmin trading community largely went by the name Bananja or Vira-bananja, which maintained its own military to safe guard transport service. Contemporary genetic studies suggest that by the time of Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas, the ruling class (Kshatriyas) were drawn from marrying outside their caste and eventually, the mixing of the population with lower caste & tribal communities halted thereafter.

Costumes and Jewellery at Kamalishwara Temple Jalsangvi built by Vikramaditya VI, Western Chalukya Dynasty, 1076-1126 CE

Depiction of costumes of man and woman from Eastern Chalukya sculpture, Alampur

HOYSALA EMPIRE (1026 CE – 1343 CE)

The constant war between Cholas and Western Chalukyas leads to weakening of both dynasties, marking the rise of Hoysala Empire in Karnataka. Hoysalas governed most of Karnataka, minor parts of Thamizh Nadu and parts of western Andhra Pradesh and Telangana between the 11th and the 14th centuries.

Panel depicting Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana (1110-1142), Channekasava Temple, Belur, Karnataka.

Hoysala kings, who appear to have been agriculturists turned royals, supported pastoral Vokkaliga community and their settlements to promote agriculture in the state. Hoysala kings also exempted the Vokkaligas from paying house tax and inducted members from the community in military services. Expansions of Hoysala territory in Thamizh kingdoms saw large scale migrations of Thamizh people who were appointed as as officers and soldiers of the empire and were given land concessions. In the Hoysala period Brahmins continued to serve the state in both civil and military positions of authority other than their traditional roles as priests. Brahminical temples enjoyed royal patronage and were not only associated with religion but served as complex institutions related to fiscal, political, and cultural needs. Although Brahminism enjoyed popularity in Hoysala society, it was influenced by three philosophers – Basavanna, Madhavacharya and Ramanuja. Lingayatism grew significantly by 12th century with association of Basavanna. Madhavacharya criticised the teachings of Adi Shankara and argued the world is real and not an illusion and his Dvaita Vedanta which countered Adishankara’s Advaita, gained popularity enabling him to establish up to eight mathas in Udupi region. Ramanuja too criticised Advaita Vedanta, preached the way of personalised devotion or bhakti and emerged as the most instrumental exponent of the Sri Vaishnavism tradition. Sri Vaishnavism is based on philosophies derived from Vedas and Divya Prabandham.

Icon of Ramanuja, Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangam, Thamizh Nadu

2ND PANDYAN EMPIRE (1212 CE – 1345 CE)

Pandyas, credited to be the oldest among the three ancient Dravidian kingdoms dating up to the first Sangam, reestablish their territorial authority in medieval period by 13th century. The discriminatory caste stratification continued to prevail under the Pandyas, who established the largest empire in Thamizh Nadu after the fall of Cholas. Following the traditions of Pallavas and Cholas, Pandya rulers continued to grant tax-free lands to the temples and the priestly Brahmins. Valankai division continued to occupy high positions in the military services of the Pandyas. Vellalas continued to enjoy their socio-economic status under the Pandya rule. Nadar community members were employed in tax collection by Pandyas and as hereditary tax collectors, the Nadars held civil authority over the lands on their control. The Parava community was associated with pearl fishing and pearl was considered as an auspicious ornament. Muthu maalai or pearl necklace featuring 104 pearls arranged on a silk string was worn by Pandya royals.

The fashion trends of medieval Pandya kingdom reflected the costume culture as found in imperial Chola kingdom. Clothing was largely unstitched; however jewellery was elaborate and exquisite. The length of pudavai worn by women covered the legs till ankles. Pudavai featured elaborate pleats and drapery. Pudavai continued to remain a garment that covered only the waist and not the upper-body. However breast-bands or Kachchu are frequently depicted in medieval Pandyan arts.

Costumes & jewellery depicted in sculptures from the temple archives of Meenakshi Temple museum, Madurai. Image: Keith Stanley

A civil war broke out between Sundara Pandya and Vira Pandya who were the sons of king Maravarman Kulasekhara Pandya. Sundara Pandya invited Malik kafur of Delhi Sultanate to invade the country. In 1311, Malik Kafur’s army drove away Vira Pandya and conquers Pandya Nadu. About half a century later Vijaya Nagar rulers defeated the sultanates and brought the Thamizh country under their rule.

KAKATIYA DYNASTY (1163 CE – 1323 CE)

A 10th century inscription of the Vengi Chalukyas suggests that early Kakatiyas served as military generals to Rashtrakutas. Kakatiyas were an indigenous Andhra power who established their sovereign rule in Andhra region in 1163 CE and ruled till the first quarter of 14th century. One of the prominent features of Kakatiya rule was the emergence of Shudras as a political elite and the other social groups accepted the superiority of Kakatiyas as rulers at a time when rest of the Indian subcontinent was rotting with the evil of Brahminical caste system. Most of the Kakatiya records do not mention the varna (social class) of the family, but the ones that do, proudly describe them as Shudra. The Kakatiyas also maintained marital relations with other Shudra families, such as the Kotas and Natavadi chiefs. Caste itself seems to have been of low importance as a social identifier however the Kakatiya rulers identified themselves as Shudras in ritual orders. Kakatiya rulers promoted egalitarianism and anyone, regardless of birth, could acquire the Nayaka title to denote warrior status. This period marks the emergence of sub-castes of Andhra Brahmins divided on the basis of regions such as Velanatis, Veginatis and Mulakanatis, besides Srotriyas and Niyogis. Native Telugu language inscriptions replace Kannada in Andhra region for the first time in the reign of Kakatiya ruler Prataparudra I.

Panel depicting costumes in Kakatiya kingdom, Warangal Fort, 12th century CE

People in medieval Andhra continued to wear unstitched garments and sewing didn’t gain popularity. However, women did wear bodice known as kolaka or kanchuka. Clothes were mainly made of cotton although silk was used by elite sections. Turbans were common and draped in a variety of styles. Ornaments made of gold, silver and other precious stones were popular among every gender. Sandalwood paste was the most common cosmetic followed by natural perfumes. Flowers were popularly used to decorate the hair. Eye-salva or anjana made of black antimong powder was not only worn to enhance beauty but for superstitious reasons too.

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond, which is now among the jewels set in the British Crown, was mined and first owned by the Kakatiya Dynasty.

The prosperous Kakatiya kingdom attracts the attention of Delhi sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji by early 14th century. Although the initial attacks were met with resistance, the last sovereign ruler of Kakatiya dynasty, Prataparudra-deva accepts the position subordinate to the sultanate at Delhi. With the demise of the Kakatiya dynasty in 1323, several regional kingdoms emerge along with the first Deccan sultanate of Bahamani.

All images are sourced from WikiCommons unless mentioned otherwise.

The post Influence of Caste System in Clothing – Medieval South India Before Sultanates appeared first on Purushu Arie.